Saying Yes to Brokenness: A Reflection on the Blessed Sacrament

by Alexa T. Dodd

A few weeks ago, I was the last to receive Holy Communion during Sunday Mass. As I came forward behind my five-year-old son, our deacon leaned toward me and whispered, “I’m going to give you a host that is slightly broken. So just be very careful with it.”

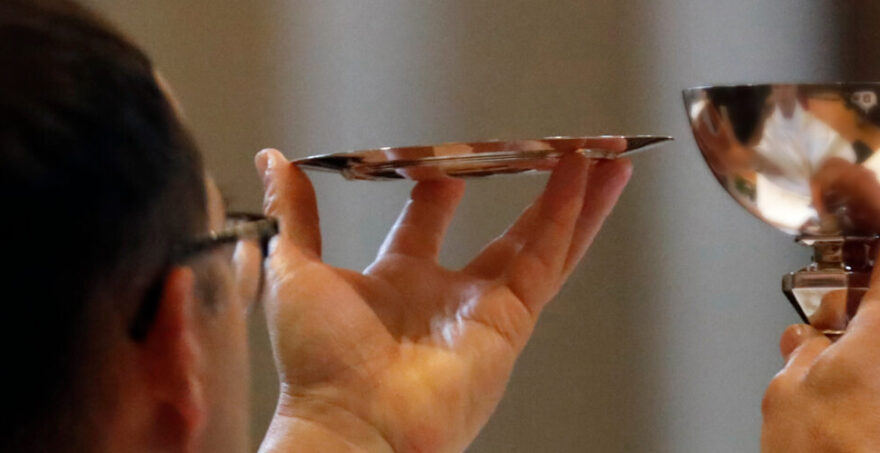

As he raised the host, I saw that it was cracked down the center, and as I brought it to my mouth, I could feel the fragile fibers of the bread. I was conscientious of how I held it, meticulous about keeping any crumb from falling.

When I made it back to the pew, I knelt in prayer for a long time, feeling as though God was trying to speak to me through this experience.

I knew our deacon had probably given me that host because I was the last person in line and he wanted to avoid putting the broken host back in the Tabernacle. But the words he’d spoken to me—how they’d startled me out of the predictable routine of standing in a Communion line—seemed almost like a riddle or a proverb. A truth about the faith I was meant to contemplate.

Indeed, the experience of receiving the broken host had rekindled my reverence for the Eucharist; the need to be so careful had reminded me of the utter sacredness of the Sacrament. My whole body seemed awakened to the truth I often take for granted: This is your Savior.

I’ve been thinking about this experience for weeks now. I know that it is partly in my nature as a writer to try to glean meaning from it, to see it as a sign of something more. But isn’t that exactly what a sacrament is? A sign of grace that simultaneously imparts grace. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church states, a sacrament is “the visible sign of the hidden reality of salvation” (CCC 774).

The broken host reminded me of the beginning words of the Consecration: “He said the blessing, broke the bread and gave it to his disciples…” Jesus’s breaking of the bread not only points to his sacrifice on the cross—where His body is broken—but makes present the one and same sacrifice. By his words that transubstantiate the bread into His body, the breaking of the bread re-presents to us the breaking of His body on the cross.

And yet, in the breaking, every piece, every fragment of that bread, and every drop from the chalice is the fullness of His body, blood, soul, and divinity. This is why I had to hold the host with such reverence—not because breaking it would somehow lessen its holiness, but because every crumb of it was the fullness of my Savior.

And herein, I think, is the paradox, the essential aspect of this experience that stands out to me: That I, who am broken—with sin and suffering—was asked to hold my broken Lord, to, in a sense, care for Him.

Every time I go to Mass—and not just this occasion that drew my attention—I am asked to witness my unworthiness even as I receive the King of the Universe. I am asked to remember that Jesus was broken for my iniquities and that I am only made whole by that breaking, by receiving into my body His body, broken for me. I am asked to love the Lord and to make myself vulnerable by accepting His perfect vulnerability.

It was as though God illuminated, in that brief exchange with our deacon, the truth I often overlook. Perhaps it stood out to me all the more because, lately, I have been very aware of my own brokenness.

Last year, I suffered an early miscarriage. Since then, I’ve struggled to overcome a sense of inadequacy about my own body.

The words of Consecration—“For this is the Chalice of My Blood…which will be poured out for you and for many”—have been a source of comfort for me as I contemplate what it means to shed blood in the context of motherhood. In a sense, the blood of my miscarriage became a conduit for that child’s salvation, though it was far earlier than expected or desired.

But recognizing that child’s joy in heaven does not diminish the pain of losing him or her. Within the last year, I have asked God why. I have struggled to rebuke the half-conscious thought that I lost that pregnancy because I did not deserve another child, that I was not worthy of them and all the joy and suffering their life would bring.

But it seemed, somehow, in the moment of receiving that broken host—of specifically being asked to take our Lord carefully—that He was signaling my worthiness.

As though He were saying, “I trust you with everything that I am. You are worthy because of me. You are enough because of me.”

As though He were asking—as He asks at every Mass—“Do you trust me? Do you trust that I am enough?”

I want my answer to be yes.