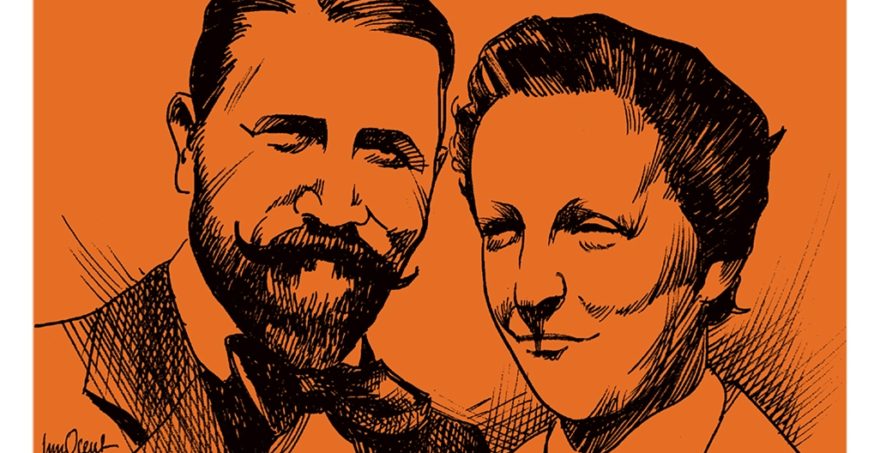

Salt and Light: The Spiritual Journey of Élisabeth and Félix Leseur

By Bernadette Chovelon

Félix and Élisabeth Leseur were married in Paris in 1889, to the joy of their friends and family. The story of their marriage and what came after can be found in Bernadette Chovelon’s Salt and Light: The Spiritual Journey of Élisabeth and Félix Leseur. Originally published in French, it is now available in an English translation by Mary Dudro.

It was a match of mutual love and admiration; unfortunately, what began as a marriage of true minds found unexpected impediments. Élisabeth’s emerging, ultimately chronic, ill health and infertility drastically changed the landscape of their marriage. Also painful to Élisabeth was the discovery that Félix was only a shell of a Catholic. At the time of their engagement, he outwardly practiced to please his mother, but inwardly he considered himself an agnostic. Over the course of their marriage, he became increasingly anticlerical and sought to draw Élisabeth away from the faith. It would not be until her death at age 47 that Félix would come to understand her faith. After Élisabeth’s passing, he read her diaries and correspondence, finding in them the depth of her love for God. This loss and revelation became the seed of his own reversion to the faith of his childhood, which would eventually lead him to become a Dominican priest.

Readers may find echoes of Sheldon Vanauken’s A Severe Mercy in this spiritual biography, as it traces a married couple’s uneven paths to Christ. As with Vanauken, one could argue that Félix had to lose his wife to save his soul, which is a weighty mystery to ponder. As Catholics, we believe that God works out our salvation through our personal vocation. Married Catholics might hear this truth and imagine it means they will live together as a happy couple, traversing the straight and narrow path side by side and hand in hand. But in reality, the mutual grace of marriage sometimes means a deep loss (as with Félix) or offering your suffering for a good you will not live to see (as Élisabeth did).

Élisabeth’s life and spirituality also call to mind the Little Way of St Thérèse, as that way might manifest in a layperson’s life. Élisabeth lived a life of frequent contemplation but also recognized her duty to be in the world. She joined her husband in his reading and shared in his enjoyment of theater, travel, art, and politics to the extent her health allowed. Lacking children of her own, she poured out her love to a wide circle of friends and those in need. When declining health forced her to do less as time went on, she adapted rather than try to force herself to activities she could not maintain. She writes in her diary: “It is quite clear to me that the divine will for me is not in action. Until further notice, I must confine myself almost exclusively to prayer and endeavor to possess more the spirit of sacrifice” (138). She also made it her habit to avoid arguments with her husband about religion, whenever possible. As Félix would later read in her diary, she told herself: “Let us not think that we hasten the coming of the Kingdom of God for souls by our personal action. As long as the Divine hour has not come, our efforts will be in vain, or rather they will be but an active prayer, an appeal to the one who transforms and saves” (180).

It is tempting to compare Élisabeth to St. Monica, also the patient wife of an unbeliever, but such analogies are unfair to Félix, who despite his unbelief appears to have frequently and tirelessly laid down his life for his wife in their marriage. He respected her opinions and treated her as his intellectual equal. He gave up his dream of living and working abroad because he feared it would be bad for her health; he would arrange for a priest to come hear her confession when she was ill. Both Leseurs, therefore, offer an example of what makes a marriage work, and what makes for a happy one: mutual passion, respect, and shared interests perfected by mutual self-gift.

Chovelon’s prose feels at times old-fashioned, though some of that may be the effect of reading a work in translation. I found myself frustrated in places because the modern author seems to limit her language and perspective to an early 20th-century viewpoint. She speaks of Élisabeth’s poor health without ever identifying its cause (hepatitis, I discovered elsewhere); Chovelon likewise doesn’t clarify that a relapse of the cancer was the cause of Élisabeth’s death, or explain whether the couple’s infertility was a result of an inability to conceive—or if they chose not to have children because of her illness at the recommendation of her doctors. Specifics like this are relevant for the modern reader, and their inclusion can make the distant holiness of a saint more relatable and accessible. Still, this biography does a good job of pointing the reader to Élisabeth’s diaries and letters as further reading, and its style issues don’t obscure the heart of her story.

This is good because their story still feels timely and relevant. Infertility, differences in religious beliefs, and chronic health issues are all-too-common crosses carried by married Christians today, and we need models to help guide our actions. In the case of saintly examples, a variety is best, since even the struggles of the Leseurs demonstrate that solutions that work well in some situations would work less well in others. As I read of Élisabeth’s patient approach to evangelizing her husband, I couldn’t help but think that her response to a difference of faith may only be possible for a couple without children: if they had been granted their desire of a family, surely their differences would have come to a head over how that family would be educated. I was simultaneously encouraged by their example and struck by how many ways there are to love God in marriage. There is no one model of Christian marriage; holy marriages are as diverse as holy people, and we would benefit from having this diversity reflected in the saints we celebrate throughout the liturgical year.

The story of the Leseurs is a poignant example of why laypersons have long been underrepresented in the calendar of saints – and why more work is needed to bring their stories to light. Many great saints have been canonized because they had religious orders to manage the multi-year canonization process, spreading the word and encouraging local devotion. Élisabeth, on the other hand, had no such organization; she had only Félix. On the strength of her writings and the testimony of those influenced by them, she was declared Servant of God in 1934. Félix, who managed the publication of her papers, tirelessly worked for her cause, but by the 1930s he was already advanced in age. When the Second World War rolled over the continent, any gathering of personal testimony for her case was put on hold. The cause for her beatification appears, therefore, to have largely died with her husband. In recent years, however, an international organization called Élisabeth Leseur’s Circle of Friends has been formed and has applied to be made the actor for her cause. I hope they succeed in renewing progress in her case; books such as this one should help make the light of this couple shine a little more brightly.

About the Reviewer:

Sara Sefranek is an English teacher turned homeschooling mother of four. She lives in Colorado with her family.